By Tara Heffernan & Felix McNamara

His hells are always genuinely frightening and credible, his heavens scarcely believable at all.—Robert Hughes on Goya, 2003.

For all their motley external diversity, they are united by their deep bond with carnivalistic folklore.—Mikhail Bakhtin in Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, 1929.

Between the acknowledgements and the first chapter of his 2003 book Goya,1 art critic Robert Hughes wrote that, following his near-fatal car crash on a desert highway in Western Australia, his body was smashed “like a toad’s,” half his skeletal structure fucked. Over the course of seven months’ hospitalisation, he faced “prolonged narrative dreams, or hallucinations, or nightmares” in which he dreamed of Goya.

The monograph positioned Goya on the ambiguous edge between pre and post-Enlightenment worlds, a place particularly complex for Spanish bourgeois liberal intellectuals who had to contend not just with a Monarchism that refused to resolutely die, but also with the widely disillusioning tyranny of the supposed (or partial) liberator Napoleon, whose Spanish campaign was portrayed in Goya’s The Disasters of War (1810-1820). In Hughes’ book images of such realist political horror are pages away from paintings with themes we might now associate closely with cinematic horror: the supernatural, superstitious, black magic, the demonic, the pagan. But a crude division between secular Enlightenment rationalism and pre-Enlightenment religiosity is contested not only by Napoleonic demons but by the Enlightenment’s debts to Christianity, and by the dynamics of “reason” and “unreason”2 that existed internally within paganism, and within Catholicism as it absorbed or made room for folklores.3 Hughes wrote:

…witchcraft was a continuous presence in Goya’s imaginative life. But was it witchcraft itself that so fascinated him—the practice of enchantment, white and black magic acting upon reality, experienced by Goya as a fact of life in the real world—or was it the peculiarity of the social belief in it, distressing a rationalist artist as a vestige of a world that was better off without such superstitions? Affirmation or denunciation? Or (a third possibility) did he view witchcraft as a later Surrealist might, as a strange and exceedingly curious anachronism that bore witness to an unreformable, atavistic, stubborn, and hence marvelous human irrationality?4

As “there is little sign of ideological or patriotic preference in his choice of subject” Goya’s oeuvre offers no easily parsed dogma but rather a material, earthly universe in which the pre-modern world and its spirits bear their weight on the modern and secular; a universe whose allegories may be counterintuitive and still apparently profoundly contemporary.

Hughes’ famous car crash as an event5 in-itself speaks to this contradictory tension: the car crash is profoundly modern, and yet it produces disgusting corporeal terror, the likes of which are supposed to be overcome by the drive now referred to in part as “refinement culture,” a logic which for some involves leaving the body (or at least its ageing processes) behind entirely. And yet the car crash, like Goya’s violent figures who tormented Hughes on his near death bed,6 remind us that not all will bow to refinement, and some forms of the “impure” bear fangs.

In American filmmaker Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018), a vehicular decapitation is but one of many of the auteur’s Goyan imageries, defined often by chiaroscuro, a genre of facial distortion, and invocations of the demonic and pagan. This is not to overemphasise a formal equivalence, even in the case that it were fair to qualitatively “compare” the imagery of cinema with that of eighteenth and nineteenth century painting, or even painting in general. What this pair articulate is a consciousness of historical tensions, a present pulled in different directions, temporally self-contradictory.7

Aster’s ‘Covid neo-Western’ Eddington (2025) has been met with similar polarisation to that of his last feature, Beau is Afraid (2023), furthering both literal and metaphorical themes of family—specifically the disintegration or mutation of the bourgeois nuclear family and its gender roles and psychologies—evident across all Aster’s shorts and features (before Beau was Hereditary [2018], Midsommar [2019], with short films including Munchausen [2014] and the particularly notorious The Strange Thing About the Johnsons [2011]). Eddington is also the most explicitly “political” of Aster’s films, not in the sense of offering any doctrine less ambiguous than that which might be claimed as “message” in his prior work (another trait shared with Goya); Eddington is rather a continuation of Aster’s established interests but in a hyper-politicised cultural setting: a small American town8 torn between a performative liberalism and a naive populism, each positioned as pawns against the real power of tech-monopoly, to which any ideology can seemingly serve as tool.

Despite Eddington’s explicit Trumpian chronotope, Aster’s entire body of work is fundamentally of the Trump era. This of reveals a relatively complex view in these films of what the Trump era—understood as the uninterrupted world-in-general since 2016—is or might be: the birth pangs of what we’ve known as “neoliberalism” making way for the hegemonic Next, placeholder titled by various terms which all invoke a “return” of the pre-modern, a marriage of Tech and the Feudal. That this understanding of the Next we’re currently sleepwalking into evokes both a sense of futurity and of medieval, pre-modern and anti-modern revival or backsliding speaks to the features of aesthetic-ideological9 hysteria and self-reinvention via various metaphorical coloured pills which have partly defined the 2010s and early 2020s, alongside (and interrelated with) processes such as the colonisation of daily life by the smartphone and social-media. The present is undergoing an ego-death well beyond microcosmic cycles of vibe shift. Regardless of whether the Big Next is radically or un-radically different from what we’ve recently experienced, the broad sense of our culture since 2016 has been that of the collapse of an Old World and the emergence of something “Next.”1011

Aster is one of few American filmmakers grappling with a cartography of this collapse/emergence. His greatest sensibility is perhaps not formal or aesthetic, but rather, historical, a master “thematist”; the subtle sensibility of historical self-consciousness. In the painter’s (Goya’s) and filmmaker’s (Aster’s) work, the ecstasies and horrors of civilisational convulsion are illustrated by the enduring figurative and aesthetic presence within modernity12 of the pre-modern, the medieval, the pagan as ingredients for a carnivalesque-comedy-horror. This presence amounts to an image of Hell; an ultimately secular image of Hell as earthly, real, and demonic; a secular world painted with religious imagery.

Indicative of this prescient knowledge of the Big Next, Aster’s films are preoccupied with the redundancy of bourgeois narrative art and its conventions—forms that have sustained storytelling since the invention of the novel and, most important, the melodrama: an emotionally-driven form of storytelling that is neither tragedy nor comedy. The emotional life that nourished these narratives arose with the new middle class, whose leisure time and familial stability provided the conditions for their flourishing. Much has been made of Aster’s representation of the family in ruin, yet we must also acknowledge his canny channeling of the fading bourgeois assumptions that structure our expectations of familial relationships which are today rendered obsolete by increased reliance on institutional surveillance, outsourced intimacy, and the failure of the historically short-lived, restricted configuration of the nuclear family—a doomed byproduct of industrial capitalism, urbanisation, and state policies that privileged small, self-sufficient household units over extended kinship networks. Indeed, Midsommar begins with the murder-suicide of the protagonist’s family at the hands of her mentally ill sister. The interior of the suburban home, the crime-scene, is of a bygone era, reminiscent of post-war American prosperity. Its rooms are enveloped in patterned wallpapers, family portraits, and floral fabrics. In our world, this family is already dead. The nuclear family, the final bulwark against total atomisation, was always too small—too easy to annihilate.

A recurring structural conceit in Aster’s films is the presence of characters’ creative pursuits. These reflect the uses (and abuses) of art and play in a philistine culture in which art has been, at least superficially, untethered from its higher aims in spiritual and sensuous life. Throughout Aster’s oeuvre, the practice of art, craft and drawing feature typically as feminised, quasi-therapeutic tools with ever-diminishing returns. In Hereditary, which was filmed on a custom built set resembling a dollhouse,13 after Annie’s mother dies, she recreates the scene of her final days in the mildly twee miniature Hospice. Later in the film, when Annie’s husband discovers her assembling a miniature of her daughter’s decapitation, she gets defensive, arguing “it’s a neutral view of the accident.” In his more recent film Eddington, the idleness of the child-like, emotionally stunted Louise Cross is broken only by the creative act, the crafting of rosy-cheeked, mutant dolls—overt manifestations of the unacknowledged trauma of childhood sexual abuse. They sell well, her complicit mother boasts. Art, then, is a hobby which materialises unexamined trauma in twee (quite aesthetically impoverished) forms, legitimised by humble monetary gain, or—in the case of Annie’s arty miniatures—cultural prestige.

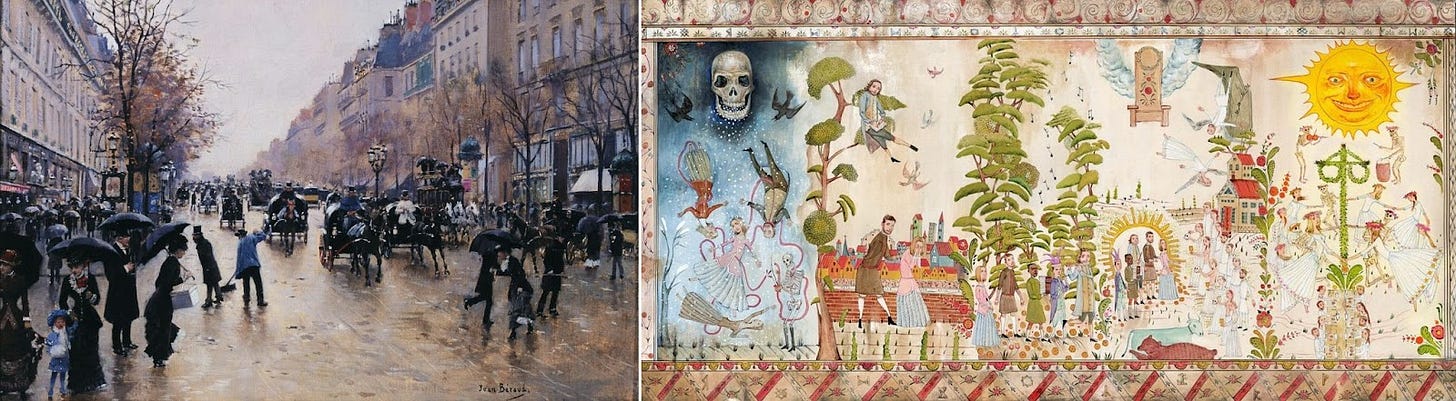

Despite the pervasiveness of pseudo-culture and art therapy, Aster respects the potency of art and storytelling. Midsommar opens with the still shot of a mural that foreshadows the events of the film. Created by New York artist Mu Pan, the mural employs a flat, decorative style, recalling both Swedish folk art traditions and the linear, narrative quality of medieval manuscript and tapestry art. The naïve perspective, ornamental borders, and rhythmic patterning offer a hybrid of vernacular folk aesthetics and early European allegorical illustration. This flatness is crucial. It tells multiple stories, of the murder-suicide, the fate of the students, the protagonist’s crowning as May Queen, all at once. This iconographically laden visual vocabulary is unlike—as Leon Battista Alberti theorised the Renaissance innovation of single point perspective—an open window onto the world, which carried the ideological assertion of modern and humanist individualism through its singular vision.14 Rather than elevating the cultivation of individual psychological insight, the mural speaks to a symbolic economy closer to medieval allegory, where terror and ecstasy are entwined within the same decorative field, and where art operates as the carrier of communal memory, prophecy, and moral order, not a record of private perception.

The motif of windows and mirrors in Aster’s films—diabolically culminating in the smart-phone screen in Eddington—suggest a keen awareness of the art historical significance of these devices, used by artists to warp or extend perception from the early modern period onward. As the Italian futurists understood, though the interpenetrative technology of the window separates the internal and external worlds, this thin layer of glass is more vulnerable than one might imagine, both to the threat of nature and the chaos of the city. As Dani howls at the death of her family, the camera dollies through the window behind her into a harsh night snowstorm: the howl of nature. Later, on their journey to Sweden, a blue sky patterned by an idyllic dotting of clouds is framed by the ovaloid airplane window. The tranquility is broken by jarring turbulence.

In the more conventional scenes in Midsommar, Aster uses mirrors to collapse multiple perspectives into one—a trick that, on the surface, visually permits the audience to witness each side of the conversation, to see what each character sees. It recalls the use of mirrors in modern paintings, such as Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882), which displays both the subject (a bar maid), and the bustling scene she faces, reflected in a mirror behind the bar. Aster uses this trick in the apartment scene following the party during which the planned trip to Sweden is revealed, blindsiding Dani. She attempts to calmly talk about her feelings and action a resolution. This is met with limp indifference from her meaty, everyman boyfriend. Rather than emotionally charged or revealing, this impasse signals the impotence of bourgeois introspection. Not only do the characters not mean what they say, but they don’t have the self-awareness to understand their desires and motivations, or those of others. Dani follows the therapeutic script to manage her intense bereavement, while her boyfriend meanders through life with little ambition or agency, only capable of expressing ambient hostility and occasional signs of adolescent amorous desire. Despite the visual clarity, the only certain revelation is the relative futility of bourgeois storytelling and representational convention under present conditions.

When conversation is in decline, so too is the art that stems from the observance of intimate social life. It becomes recording without insight. As many commentators have noted,15 this soulless recording is perhaps best demonstrated in autofiction, now an autistic mapping of minor grievances and superficially rendered social types, emotionally managed to the point of total depersonalisation. To “see” is no longer to perceive, it is only to make others bear witness.16 This is not enough to sustain the form. The spiritually bankrupt anthropology students in Midsommar—bent on recording, reporting and disseminating their findings in peer-reviewed journals—are killed. They cannot comprehend what they have walked into. Their liberal world view, buffered by feigned cultural sensitivities, has ill prepared them.

Scenes of public life—cosmopolitan street scenes, or shared leisure time—preoccupied painters of the new middle class in the nineteenth century. We witness these visions, and the respect for bourgeois self-understanding they conveyed on the canvases of artists like Jean Béraud or Georges Seurat. Their subjects are not united as a group, but share the street, or river-side, as individuals or subsets; together, though often preoccupied with their own rich inner worlds. Midsommar traces the beginning of the backslide from the bourgeoisie subject to the pagan peasant, invoking Goya, and following conventional horror movie ‘descending’ arc. In a telling early scene, on the outskirts of the Hårga’s land, the students consume hallucinogenic tea and sit together waiting for the effects to wash over them. It resembles the sleepy scene in Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884), a Post-Impressionist painting depicting the working class and petit-bourgeoisie of Paris at leisure, partially unclothed and unselfconscious; something of a heaven to Goya’s and Aster’s hells. Aster’s scene is, at least implicitly, against sociability. Despite the drugs, these characters are unable to relax. They are simultaneously highly self-conscious and terrified of getting lost in themselves. “I don’t want new people,” the Beevis phenotype wails as a friendly man passes the group.

One might imagine Aster as the heir to American filmmakers like Woody Allen, Todd Solondz, or Charlie Kaufman, yet his work has more in common with the blood-soaked, orgiastic late-capitalist chaos of Ryan Trecartin or Greg Araki (both of whom pit pre-modern carnivalesque excess against the sterile, stylised aesthetics of Y2K mise-en-scènes).17 Though Allen’s, Kaufman’s, and Solondz’s films probe at the collapse between public and private life, the triumph of the therapeutic, and the grating nature of performative professional identities and cloying middle-class sensibilities, their characters have more agency than Aster’s. For the former’s protagonists, a retreat from the humiliations of a degraded public life is still possible, even if it is only in the mind. These filmmakers have more in common with the Russians, with Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Anton Chekov, who were similarly concerned with men who were terrorised by (or instruments of) bureaucracy, the state, administration, and poshlism.18 While these concerns are present in Aster’s films, there’s something more hopeless about his antiheros.

The carnivalesque pervades Aster’s worlds. Boundaries collapse, collective ecstasies and horrors mingle. Indeed, in Midsommar, death, procreation, and mourning are ritualised and shared. We see the dramatisation of a world turned upside down,19 where traditional formations collapse and social order dissolves into grotesque parody. Drawing on the medieval and folk traditions described by Mikhail Bakhtin, the carnival is at once disruptive and regenerative, a space where fear and laughter blur, and where the grotesque body mocks the pretensions of authority. In Beau Is Afraid, and in Eddington, this aesthetic links the pre-modern rituals of inversion to the unruly energies of contemporary mass culture, mass politics, and populist spectacle, suggesting, like Goya, that the chaotic breakdown of order is not only medieval but also constitutive of modern life.

The street scenes in the first act of Beau is Afraid are a true descent into hell. Outside his apartment is a nightmare world populated by monsters, murderers, and festering corpses. He witnesses frenzies of drug induced psychosis, gun violence, rape, and murder in broad daylight. In a scene that literalises the breakdown between public and private life, after a mishap with his keys, the chaotic cast of the street spills into his apartment. Indeed, public life has collapsed, and there is no salvation in the private realm (the home or the mind).20 It is slowly revealed that every dimension of Beau’s life is monitored by his mother, who runs a sprawling corporate empire focused on pharmaceutical and consumer products.21 Liberal-democratic society is figured here as matriarchal, resembling pre-modern systems of communal control in which conformity, safety, and emotional management are enforced at the expense of individuality. Feminine forms of control, previously figured as private matters, extend to public and professional life. For Beau, and all subjects suffering under late capitalism, the language of safety and therapy becomes the means through which every aspect of life is managed and regulated.22 And yet, chaos reigns.23 Like the peasants and vagrants depicted by Goya—aside from those liberated by the semblance of freedom that comes with madness—public (and so-called private) life requires constant vigilance. Concerns of survival and self-preservation expend all mental energy.

The fate of Joaquin's "Joe Cross" at Eddington's end appears as allusion to Nietzsche's paralyzed psychosis, sadistically curated by his political-opportunist sister Elisabeth (in Eddington, Joe's step-mother, Dawn, whose daughter's tragic anti-marriage to Joe invokes also Nietzsche's relation to Lou Andreas-Salomé). The film's final scenes can then be read as a re-framing of Joe as something of a low-IQ Nietzsche, searching for a(n ultimately self-determined moral) horizon in a world with many dead or dying gods,24 whose "tremendous" and "gruesome" "shadows"25 nonetheless remain cast. Like many contemporary self-proclaimed Nietzscheans, Joe is a hero of the body as opposed to the mind, and as such, his demise is an inversion of Nietzsche's; instead of a traumatic image26 irreversibly scaring his thought, a literal knife through the skull kills Joe's body but not his prison of consciousness. This insinuation to Nietzsche implies two things on the level of "meaning" in Eddington: firstly, the contemporary-historical frame of 2020—as a cataclysm punctuating all readings of both the 2010s and the 2020s in which we still live—is, in its apparent hyper-topicality, a hint that ours is still the time of Nietzsche's, that Kojève might be right that we are living forevermore on the 14th October 1806.27 Furthermore, Aster's injection of the spirit of Nietzsche into the Average Joe, Joe Cross, with a cross to bear, is a maneuver that might be at odds with various casual references to Eddington's "reactionary” tendencies; Nietzsche's life's work and life's example is apparently not (necessarily) a how to (exist) guide for (would-be) Aristocrats,28 but a universal question for the Universal Joe: “what's the horizon?”

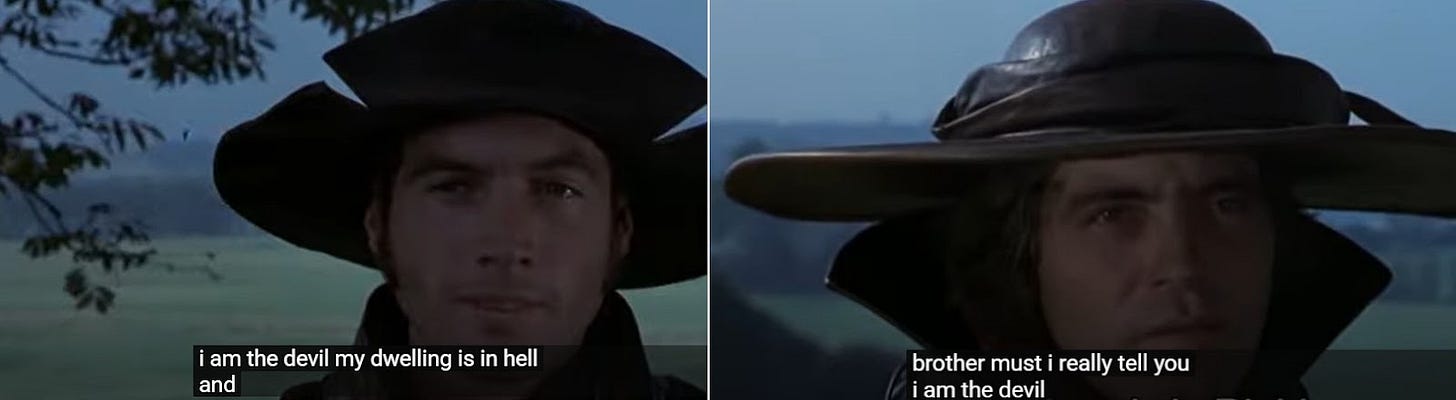

Any mode of bankrupt polling could surely (and nonetheless more or less truthfully) point to a popular assumption that we are in or entering some manner of “Dark Age.” As per Pasolini’s 1972 The Canterbury Tales, the Devil is an NPC walking the earth. Heaven, Hell, and Earth are collapsed in on each other; their characters dialogue, our underworlds are earthly. Nietzsche remains something of a partial-saint to our secular-pagan world, “pagan” in the sense of Dave Hickey,29 pagan in the sense that godlessness makes for many gods, who in the case of spirits like Jeffrey Epstein or Michael Jackson, need not conform to Judeo-Christian, bourgeois morality. We don’t know, and Aster, like Goya, like many mentioned here, can help us to know this.

Published the year Hughes’ son Danton died by suicide.

Or maybe “Apollo” and “Dionysus.”

Not to mention the Reformation-Era Protestant critique of Catholicism’s “paganism.”

Further: “Goya tended to paint according to commission. There is little sign of ideological or patriotic preference in his choice of subject. Even a partial list of Goya’s clients before the defeat of Napoleon in Spain shows a fairly even distribution of political views between conservative Spaniards, Spanish liberal patriots, and French sympathisers. In the first category, those he painted included the duchess d’Abrantes, Juan Agustin Cean Bermudez, the conde de Fernan Nunez, Ignacio Omulryan, and of course Fernando VII.” (pg. 11-12)

And “invention” as Paul Virilio would say.

An experience which as described in the book sounds somewhat like the solipsistic and inescapable nightmare sequence that is Beau is Afraid (2023).

Fascism, in its original context, was and remains argued as: modernist, Protestant (anti-Catholic), Catholic, Pagan (anti-Christian), Positivist (anti-Pagan), Socialist, Pure Capitalist, Left-Wing, Right-Wing, Both-Wings, Third-Wing, Ironic (nihilistic), Sincere, Etc. And what of our isms now?

A place often argued to be at odds with modernity, as opposed to being, as in both Eddington and Rem Koolhaas, the canvas of our Tech-“Future.”

See Udith Dematagoda and Christos Asimatos, “The Ideological Aesthetic: the political as inevitable and epiphenomenal”, Angelaki: A Journal of Theoretical Humanities 28, no.5 (September 2023), 39-55.

An additional complexity of the apparent decline, re-invention, mutation or “sublation” of neoliberalism is that it raises the problem that neoliberalism has acted since the end of the Cold War as a synecdoche for Liberalism and Enlightenment in-themselves; previous iterations of liberalism are beyond the presentist memory, and as such, nostalgia for earlier liberalisms tends to be labelled, both pejoratively and by the ideologue themselves, as a kind of radical Right- or Left-ism.

Which might never come; we might still be living now in Ancient Greece.

Whether post- or meta- or whatever.

The “dollhouse” is, of course, important thematically. Throughout Aster’s films, characters' actions are controlled by some unseen, often feminine, larger force.

Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting (1435).

Though there’s many very contemporary examples, the prescient work of Christopher Lasch and Dwight Macdonald nailed these tendencies in 1979 and 1965 respectively. See Christopher Lasch, “The Awareness Movement and the Social Invasion of the Self” in The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in the Age of Diminishing Expectations (W.W. Norton and Company, 1979), 16-21; and Dwight Macdonald, “Parajournalism, or, Tom Wolfe and his Magic Writing Machine”, The New York Review, August 26, 1965, See.

Indeed, in Eddington, the mirror is replaced by the iPhone—its extension of perception manifests in the obsession with recording, livestreaming, going viral. To see is never enough. First hand experience is only useful insofar as it can be instrumentalised.

Or Lars Von Trier, particularly in their shared pagan respect for the horrors of nature.

Poshlism, which can be roughly translated to smug-philistinism, describes a deeply ingrained banality, vulgarity, and spiritual emptiness. In his post-humously published lecture “Philistines and Philistinism” Vladimir Nabokov explains its significance in nineteenth century Russian literature as a result of Old Russia’s lingering investment in simplicity and good taste—values that were completely eroded by the pervasiveness of pseudo-culture and moral imbecility in the twentieth century. Vladimir Nabokov, “Philistines and Philistinism", in Lectures on Russian Literature (Pan Books, 1983), 309-314.

Characteristic of Aster, a heavy handed metaphor introduces this carnivalesque “upturning” in Midsommar: as the group drive to the Hårga community, the scene flips upside down.

Beau’s spiritual and intellectual weakness is largely a result of unrelenting fear and precarity.

The company logo, his mother’s initials, flashes at the beginning of the film, as though she produced the film.

As Nina Power and Benjamin Studebaker have noted, Beau is Afraid can be read as a damning critique of “the longhouse.” “Beau is Afraid,” The Lack, 4 November 2024.

Mounting infographics and therapeutic public messaging only signal further decline.

Liberalism (including Liberalism's conservative values) and bourgeois society (including both its liberal and conservative values).

“After Buddha was dead, his shadow was still shown for centuries in a cave—a tremendous, gruesome shadow. God is dead; but given the way of men, there may still be caves for thousands of years in which his shadow will be shown—and we—we still have to vanquish his shadow, too.”

The Turin horse incident.

Kojève's claim that the Battle of Jena is the “End of History.”

Hickey’s unfinished book Pagan America was summarised by Daniel Oppenheimer: “The argument was this: America at its most distinctive wasn’t Judeo-Christian or capitalist or even democratic in a simple way. It was pagan. Not an earth spirit paganism of the moors and glens, but a polytheistic, commercial, cosmopolitan paganism of the bazaar and the agora. We invested objects, people, and performances with the power of our dreams and fears, and then we organized ourselves around those idols in “non-exclusive communities of desire,” arguing about them, buying and selling pieces and images of them on the open market, trying to woo others into our camp and score points over rival camps. We were a democratic people, but to see American democracy clearly was to understand that our democracy renewed itself on a substratum of pagan devotions to movie stars, rock stars, oil paintings, charismatic political figures, football teams, ingenues, mystery novels, muscle cars, runway shows, action movies, and action painters.” Daniel Oppenheimer, “Pagan America: An Excerpt from Far From Respectable on art critic Dave Hickey’s unpublished book,” Bookforum, August 10, 2021, see.